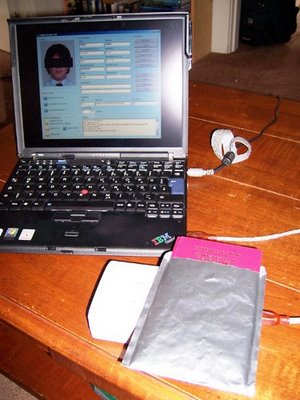

Grunwald placed the passport on top of the RFID reader and within four seconds the data on the RFID chip embedded in the passport appeared on the screen in the Golden Reader Tool template. New e-passports come with a metallic jacket to prevent someone from surreptitiously "skimming," or reading the data on the chip from afar. To allow authorities to read the data on the RFID passport chip, the passport owner must remove the document from the shield before passing it over the RFID reader. Data retrieved from an RFID passport chip gets dumped into the Golden Reader Tool template where passport authorities can examine it. Here, Grunwald has typed in random data, and a photo was taken from the internet to show how the tool works. Photo Credit: Kim Zetter

Grunwald placed the passport on top of the RFID reader and within four seconds the data on the RFID chip embedded in the passport appeared on the screen in the Golden Reader Tool template. New e-passports come with a metallic jacket to prevent someone from surreptitiously "skimming," or reading the data on the chip from afar. To allow authorities to read the data on the RFID passport chip, the passport owner must remove the document from the shield before passing it over the RFID reader. Data retrieved from an RFID passport chip gets dumped into the Golden Reader Tool template where passport authorities can examine it. Here, Grunwald has typed in random data, and a photo was taken from the internet to show how the tool works. Photo Credit: Kim ZetterThe Department of Homeland Security's agenda for streamlining the passport issuance and reading process is not without its problems.

The new RFID (radio frequency identification) enabled passports due to be issued later this year, has had it critics and most people believe that this technology used with this application is not a good idea >>> Symblogogy: Proximity Passport Perception Problems Persist (July 26, 2006).

To be honest, if information can be stored and read from an RFID chip, the information can be hacked, manipulated and used for no good.

Excerpts from Wired News -

Hackers Clone E-Passports

By Kim Zetter - Wired News - 02:00 AM Aug, 03, 2006

LAS VEGAS -- A German computer security consultant has shown that he can clone the electronic passports that the United States and other countries are beginning to distribute this year.

The controversial e-passports contain radio frequency ID, or RFID, chips that the U.S. State Department and others say will help thwart document forgery. But Lukas Grunwald, a security consultant with DN-Systems in Germany and an RFID expert, says the data in the chips is easy to copy.

"The whole passport design is totally brain damaged," Grunwald says. "From my point of view all of these RFID passports are a huge waste of money. They're not increasing security at all."

Grunwald plans to demonstrate the cloning technique Thursday at the Black Hat security conference in Las Vegas.

The United States has led the charge for global e-passports because authorities say the chip, which is digitally signed by the issuing country, will help them distinguish between official documents and forged ones. The United States plans to begin issuing e-passports to U.S. citizens beginning in October. Germany has already started issuing the documents.

Although countries have talked about encrypting data that's stored on passport chips, this would require that a complicated infrastructure be built first, so currently the data is not encrypted.

"And of course if you can read the data, you can clone the data and put it in a new tag," Grunwald says.

The cloning news is confirmation for many e-passport critics that RFID chips won't make the documents more secure.

"Either this guy is incredible or this technology is unbelievably stupid," says Gus Hosein, a visiting fellow in information systems at the London School of Economics and Political Science and senior fellow at Privacy International, a U.K.-based group that opposes the use of RFID chips in passports.

----

Grunwald says it took him only two weeks to figure out how to clone the passport chip. Most of that time he spent reading the standards for e-passports that are posted on a website for the International Civil Aviation Organization, a United Nations body that developed the standard. He tested the attack on a new European Union German passport, but the method would work on any country's e-passport, since all of them will be adhering to the same ICAO standard.

In a demonstration for Wired News, Grunwald placed his passport on top of an official passport-inspection RFID reader used for border control. He obtained the reader by ordering it from the maker -- Walluf, Germany-based ACG Identification Technologies -- but says someone could easily make their own for about $200 just by adding an antenna to a standard RFID reader.

He then launched a program that border patrol stations use to read the passports -- called Golden Reader Tool and made by secunet Security Networks -- and within four seconds, the data from the passport chip appeared on screen in the Golden Reader template.

Grunwald then prepared a sample blank passport page embedded with an RFID tag by placing it on the reader -- which can also act as a writer -- and burning in the ICAO layout, so that the basic structure of the chip matched that of an official passport.

As the final step, he used a program that he and a partner designed two years ago, called RFDump, to program the new chip with the copied information.

The result was a blank document that looks, to electronic passport readers, like the original passport.

Although he can clone the tag, Grunwald says it's not possible, as far as he can tell, to change data on the chip, such as the name or birth date, without being detected. That's because the passport uses cryptographic hashes to authenticate the data.

When he was done, he went on to clone the same passport data onto an ordinary smartcard -- such as the kind used by corporations for access keys -- after formatting the card's chip to the ICAO standard. He then showed how he could trick a reader into reading the cloned chip instead of a passport chip by placing the smartcard inside the passport between the reader and the passport chip. Because the reader is designed to read only one chip at a time, it read the chip nearest to it -- in the smartcard -- rather than the one embedded in the passport.

----

Frank Moss, deputy assistant secretary of state for passport services at the State Department, says that designers of the e-passport have long known that the chips can be cloned and that other security safeguards in the passport design -- such as a digital photograph of the passport holder embedded in the data page -- would still prevent someone from using a forged or modified passport to gain entry into the United States and other countries.

"What this person has done is neither unexpected nor really all that remarkable," Moss says. "(T)he chip is not in and of itself a silver bullet.... It's an additional means of verifying that the person who is carrying the passport is the person to whom that passport was issued by the relevant government."

Moss also said that the United States has no plans to use fully automated inspection systems; therefore, a physical inspection of the passport against the data stored on the RFID chip would catch any discrepancies between the two.

----

In addition to the danger of counterfeiting, Grunwald says that the ability to tamper with e-passports opens up the possibility that someone could write corrupt data to the passport RFID tag that would crash an unprepared inspection system, or even introduce malicious code into the backend border-screening computers. This would work, however, only if the backend system suffers from the kind of built-in software vulnerabilities that have made other systems so receptive to viruses and Trojan-horse attacks.

----

Grunwald's technique requires a counterfeiter to have physical possession of the original passport for a time. A forger could not surreptitiously clone a passport in a traveler's pocket or purse because of a built-in privacy feature called Basic Access Control that requires officials to unlock a passport's RFID chip before reading it. The chip can only be unlocked with a unique key derived from the machine-readable data printed on the passport's page.

To produce a clone, Grunwald has to program his copycat chip to answer to the key printed on the new passport. Alternatively, he can program the clone to dispense with Basic Access Control, which is an optional feature in the specification.

Grunwald's isn't the only research on e-passport problems circulating at Black Hat. Kevin Mahaffey and John Hering of Flexilis released a video Wednesday demonstrating that a privacy feature slated for the new passports may not work as designed.

----

In addition to cloning passport chips, Grunwald has been able to clone RFID ticket cards used by students at universities to buy cafeteria meals and add money to the balance on the cards.

----

Many of the card systems that did use encryption failed to change the default key that manufacturers program into the access card system before shipping, or they used sample keys that the manufacturer includes in instructions sent with the cards. Grunwald and his partners created a dictionary database of all the sample keys they found in such literature (much of which they found accidentally published on purchasers' websites) to conduct what's known as a dictionary attack. When attacking a new access card system, their RFDump program would search the list until it found the key that unlocked a card's encryption.

"I was really surprised we were able to open about 75 percent of all the cards we collected," he says.

Read All>>

RFID may sound like a good idea for automating the process of identification through our nation's checkpoints, but when it comes to the internal security of our country and the protection of our identity ... this just isn't the same application process as a "Mobil Speedpass" or a freeway tollway access payment verification.

Typical, the federal government remains clueless to the real issues that surround the application of this proximity technology.

As in real estate (location, location, location) the axiom for the implementation of a new technology is "application, application, application!"

No comments:

Post a Comment