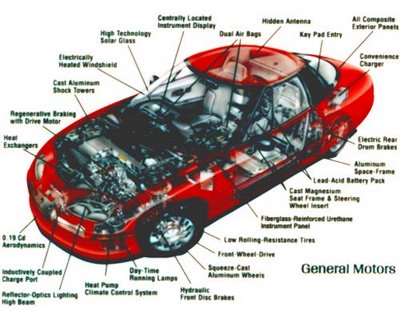

GM EV1 - World's most energy efficient production vehicle is also, by necessity , the ideal platform for advanced vehicle technology development as illustrated by cutaway showing host of new technologies it incorporates. Image Credit: General Motors

GM EV1 - World's most energy efficient production vehicle is also, by necessity , the ideal platform for advanced vehicle technology development as illustrated by cutaway showing host of new technologies it incorporates. Image Credit: General MotorsCalifornia --- land of milk and honey, designer agriculture, Sequoias, Hollywood, "from the desert to the sea", "Silicon Valley", the sixth largest economy in the world, and car-cars-cars.

One would think that since our state has such a "cutting edge" image throughout the Planet that we would be getting our arms around this issue of vegetable matter fuels --- E85. But NooOOOOoo, California, "The Golden State", currently has only four (4) fuel stations that offer a "FlexFuel" option (where E85 Ethanol fuel mix can be purchased) and only one (1) of the stations is open to the public (the other three are for use with U.S. Government vehicles and/or employees).

This glaring failure isn't because California hasn't tried in its efforts to bring alternative energy sources and cleaner air to the State, but more a matter of intent, application, and taxes. The government can not get out of its own way.

Excerpts from The Wall Street Journal via the Post-Gazette (Pittsburgh, PA.) -

How California failed in efforts to curb oil addiction

By Jeffrey Ball, The Wall Street Journal - Wednesday, August 02, 2006

OAKLAND, Calif. -- In a government parking lot by the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, California is about to launch its latest attempt to get cars to run on something other than oil.

Chevron Corp., the California-based oil giant, plans to install a small tank here soon with enough corn-based ethanol to power about 35 General Motors Corp. cars capable of burning both ethanol and gasoline. California, the nation's biggest auto market, has about 10,000 gas stations. This will be its fifth ethanol pump.

For a quarter century, California has pursued petroleum-free transportation more doggedly than any other place in the U.S. It has tried to jump-start alternative fuels ranging from methanol to natural gas to electricity to hydrogen. None has hit the road in any significant way. Today, the state that is the world's sixth-largest economy finds itself in the same spot as most of the planet: With $75-a-barrel oil, and increasing concern about the role fossil fuels are playing in global warming, 99 percent of its cars and trucks still run on petroleum products.

At a time when President Bush is advocating alternative fuels, particularly ethanol, as an antidote to what he calls America's "addiction" to oil, California's experience offers a reality check. Perfected over a century, gasoline is convenient, reliable, and, even at current prices, relatively affordable. Challengers start with big disadvantages: inadequate infrastructure, their own performance problems, and higher costs. Moving alternative fuels into the mainstream would require hard political and economic choices -- choices that even California hasn't been willing to make.

California launched its alternative-fuel drive as an energy-diversification effort following the 1979 global oil shock. When oil prices fell back, the state shifted its emphasis to fighting air pollution. Since then, California has rolled out mandates and subsidies for alternative-fuel demonstrations along with broader rules forcing the oil and auto industries to clean up their conventional fuels and internal-combustion engines. The assumption was that the one-two policy punch would induce the industries to shift away from oil.

But the market hasn't responded the way California intended. The oil and auto industries got the state to kill or water down the alternative-fuel mandates, arguing that making the technologies viable would require big public subsidies -- something most Californians didn't support. Meanwhile, the industries made their conventional products clean enough to meet the state's pollution limits.

The upshot: The alternative-fuel push has helped scrub California's air, but it has done so by forcing improvements in fossil fuels and the cars that burn them. It hasn't curbed California's oil consumption, because it hasn't meaningfully deployed alternative fuels.

California's experience shows that there are "somewhat viable types of alternative fuels available out there in the event that somebody wanted to move towards them," says James Boyd, who has been pushing for oil alternatives for more than two decades as a California environmental and energy regulator. Though politicians since Richard Nixon have called for diversifying America's energy mix, he says, "we've never had a serious effort."

----

Oil and auto companies say they're justified in resisting government mandates to roll out alternative technologies when they're not convinced consumers will buy them. Donald Paul, Chevron's chief technology officer, says California regulators essentially tell industry officials, "We know what the answer is. You guys just spend the money and everything will work fine." He adds, "History has not shown that that works very well."

----

The question today is whether the resurgence of high oil prices and the rise of global-warming concerns will give alternative fuels sustained backing. Already, ethanol, the brew now generating the biggest buzz, is hitting many of the same roadblocks that slowed California's past alternative-fuel attempts.

GM and Chevron are bickering over the ethanol demonstration project that is set to include the pump in Oakland and one near Sacramento. It's a chicken-or-egg dispute. GM, which for years has been building "flexible-fuel" vehicles that can burn ethanol but typically don't, wants Chevron to install a lot of ethanol pumps. Chevron, which estimates that installing a single ethanol pump and related equipment costs more than $200,000, wants to go slow to make sure first that consumers will buy the fuel.

When California started searching for potential petroleum alternatives following the 1979 oil shock, it concluded that methanol was particularly promising. The alcohol already was being made for industrial use. And it was derived from natural gas, which was cheap and was believed to be domestically plentiful.

The state began experimenting with a handful of 1979 Honda Civics that had been converted to run on gasoline mixed with up to 15 percent methanol. The idea was to use the methanol to make the gasoline go farther -- "Hamburger Helper," as state officials called it.

Soon California ratcheted up its experiment to include several hundred Ford Escorts that had been tweaked to run on a blend of 15 percent gasoline and 85 percent methanol, or M85. The state installed 18 methanol pumps at gas stations near state offices, divided up the cars into fleets, and told state employees to give them a whirl.

Operational problems soon arose, in part because alcohol fuels like methanol contain less energy than gasoline. The Escorts went only about 60 percent as far on a tank of fuel as their gasoline counterparts.

----

In the late 1980s, the auto industry came up with a technology designed to solve such problems: a "flexible-fuel" vehicle, able to run on either straight gasoline or an alternative fuel, which at the time was a blend of up to 85 percent methanol.

Legislation worked out in Washington gave auto makers a big incentive to crank out flexible-fuel vehicles. In 1988, with the support of California officials, Congress passed a law giving auto makers extra credit under the nation's fuel-economy standards for every such vehicle the companies built. The credits allowed the auto makers to build thirstier conventional vehicles. But they didn't require that the buyers of the flexible-fuel vehicles actually use an alternative fuel. Most of them filled up with gasoline.

That was rational at a time when global oil prices were once again falling. In California, alternative-fuel proponents shifted to a priority that had more enduring political support: cleaning up the state's notoriously dirty urban air.

----

California continued to search for oil alternatives. In 1990, as California regulators were putting the finishing touches on new clean-air rules, GM unveiled at the Los Angeles auto show a bubble-shaped car that ran on electricity and thus emitted no pollution. It was called the Impact.

State officials were enthralled. The California Air Resources Board, the state's clean-air cop, mandated that 10 percent of all new cars sold in California be "zero-emission vehicles" by 2003.

Meanwhile, California told its investor-owned utilities to do what they could to encourage the rollout of both electric and natural-gas-powered cars. The utilities were eager for the potential new market that the alternative-fuel cars presented. By the early 1990s, they were spending tens of millions of dollars each year installing natural-gas fueling stations around the state and testing new technology for natural-gas and electric vehicles. They applied to state regulators for permission to pass along those costs to customers through higher rates.

The oil industry formed a coalition that sent letters to commission members and legislators opposing what it dubbed a "hidden tax" to subsidize alternative fuels. The California Public Utilities commission ruled that, while utilities might be able to spend ratepayers' money to roll out alternative fuels in the utilities' own fleets, they couldn't spend that money to try to commercialize alternative fuels more broadly.

As a result, California utilities closed or sold 54 natural-gas stations that they had installed for customers' fleets, says Brian Stokes, manager of clean-air transportation for PG&E Corp.'s Pacific Gas & Electric Co., a big California utility. They also stopped subsidizing customers' purchases of electric and natural-gas vehicles. Though natural-gas and electric-charging stations still exist throughout California, and PG&E is working to promote their expanded use, the state's decision severely impeded their growth, he says. "To the extent that policy could have provided a sustainable market, it was nipped in the bud," he says.

----

The auto industry also opposed the electric-car mandate, arguing that the California measure was forcing a technology that wasn't road-ready.

In response, California officials repeatedly softened the rule. They ended up letting the industry comply largely with a compromise technology: hybrid cars. Hybrids have an electric motor and batteries, but instead of having to be plugged into a socket for their power, their batteries are recharged continuously during normal driving -- driving that still requires a conventional engine under the hood. Hybrids have lower emissions and get better mileage than conventional cars, but they still burn fossil fuel.

Yet the auto industry protested the move toward hybrids too. In 2001, GM sued California to block the zero-emission vehicle rule. Its suit, later joined by DaimlerChrysler AG's Chrysler unit, argued that by shifting their focus from electric cars to gasoline-burning hybrids, California regulators had turned their clean-air rule into a veiled attempt to improve fuel economy. And fuel economy, the auto companies noted, is something only the federal government has the legal power to regulate.

GM and Chrysler later dropped their suit when California officials further softened their rule.

----

Around 2000, a series of gasoline-price jumps hit California. State officials ordered a study of whether oil companies were gouging drivers at the pump. The study concluded the jumps were due not to gouging, but to market forces: Global demand for oil was growing faster than global supply. A follow-up report called for California to cut its oil use 15 percent by 2020, in part by using more ethanol and other "biofuels."

That marked a turning point in California's energy agenda. No longer was the state's goal simply to reduce the pollution produced when fossil fuel is burned. Now, as in 1979, it was to reduce the amount of fossil fuel burned in the first place.

Since then, oil companies have helped quash efforts in the California Legislature to codify that oil-use-reduction target into law.

----

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, who met Monday with British Prime Minister Tony Blair to discuss ways to reduce global-warming emissions, says he supports the oil-use-reduction goal. "I think it's a good idea," the former body builder said in a recent interview, likening it to a dieter's resolution. "If I don't say that I want to lose 10 pounds by summer, it's not going to happen by itself." He added, "Of course the fat in your body is screaming, 'Don't attack me. I love myself.' So the oil companies are screaming, 'This is terrible.' "

----

For years, gasoline in parts of the country with particular smog problems has contained 10 percent ethanol, the result of a federal rule ordering refiners to put an oxygen-rich additive in the gasoline they sell in those areas to help curb pollution. Yet studies show that while ethanol added to gasoline in low concentrations helps reduce certain emissions, such as carbon monoxide, it tends to increase some other emissions. In particular, it raises the gasoline's "vapor pressure," leading more gasoline fumes to seep out of a car's fuel system. California effectively restricts ethanol concentrations in its gasoline to 6 percent.

----

Early this year, GM launched an advertising campaign to tout the use of the corn-based fuel in those vehicles. Its tagline: "Live green. Go yellow."

Last fall, GM approached Alan Lloyd, then secretary of the California Environmental Protection Agency, and proposed an ethanol demonstration. Mr. Lloyd suggested involving Chevron, since it is based in the state. In discussions that followed, Chevron officials "wanted a very limited number" of ethanol stations, and GM wanted more, Mr. Lloyd says.

David Barthmuss, a GM spokesman, confirms that account. "Until oil companies see there's money to be made in ethanol, they're going to lobby for petroleum," he says. "E85 is asking them to give up 85 percent of what they make." He says GM hopes to persuade Chevron and other oil companies that if they put in E85 pumps, the auto industry will build the vehicles to make those pumps profitable.

Chevron recently announced a new business unit that will focus on trying to make ethanol and other biofuels viable. But Chevron's Mr. Paul says the company has learned from California's history not to rush into potential oil alternatives. "If you're going to roll out a very large infrastructure and put what could be a lot of money into it, you don't want something that you're going to have to throw away," he says.

Today there's just one E85 station in California that is open to the public. It sits beside a highway interchange in San Diego. It was opened three years ago by Pearson Ford, a San Diego Ford dealer that was convinced alternative fuels would be the next big thing. The station offers gasoline and diesel, natural gas, propane, electricity, biodiesel and E85.

What it sells, though, is mostly gasoline and diesel. On a recent morning, it was offering E85 for $3.10 a gallon, about 6 percent less than the $3.30 per gallon it was charging for regular gasoline. But, because a gallon of E85 contains about 25 percent less energy than a gallon of gasoline, the E85 actually cost more per mile. Only a handful of cars pulled up to the E85 pump.

"I would like nothing better than to turn all my pumps over to alternative fuels," says Mike Lewis, the station's co-owner. "But I'm not willing to carry the alternative-fuel flag into bankruptcy."

Read All>>

3 comments:

I hadn't seen the WSJ article - thanks for digging it out.

The big problem with ethanol in California is that, although we are the world's largest consumer of the stuff (at 6% blend we are using over 900 million gallons per year) we produce only 5% of what we use. No corn. That's a bigger problem than it may seem because you can't pipe ethanol without contamination - so ideally your feedstock is near your biorefineries.

I work with people at the BioEnergy Producers Association in your backyard (L.A.). The main mission of the group is to reduce our urban dependence on dwindling landfills. We have found that, through the use of conversion technologies, we can use our considerable waste streams in agriculture, forestry, and municipalities to provide the feedstock for environmentally clean conversion to electricity, ethanol, and/or hydrogen.

I think installing E85 pumps is a little premature for California. You can't push an "exotic" fuel on the public - there has to be some demand first. We are seeing the beginning of that because of the spike in energy prices, a hot summer, and frustration with the petro war in the Middle East.

We do have existing demand that doesn't involve the public. If we simply started replacing our imports of ethanol with "homegrown" brew that would be a sizeable accomplishment - a big money saver for the state as well as a source for "green" collar jobs - and give us time to develop consumer awareness and infrastructure.

By the time we fill our blends with homegrown ethanol, cellulosic ethanol made from waste would probably be cheaper than the bloodstained petroleum products. I am also hoping that flex-fuel PHEVs will raise MPG significantly and reduce the demand for high-energy liquid fuels.

I invite you to take a look at my BioConversion Blog at http://bioconversion.blogspot.com to learn more about the issue - the technology and our struggle with Sacramento to get needed regulatory legislation passed.

Just read your article and am glad someone else sees how silly this marketing campaign is...But I'm curious how successful an E85 station would be here in Bay Area of California, esp because I think that there are a lot of people up here who want to use the flex fuel but can't get it. Why aren't there any campaigns to market the fuel in an area that is environmentally progressive and see what kind of ripple effect we get?

Sigh...I guess the little guy is still unheard.

If you have bought a G.M. car in the last 5 years. Then you probably have a flex fuel vehicle. I have one, But what good is it. There are over 300,000 of them in this state. If I could get, I would use it. Regardless of the cost.

Frustrated

Post a Comment